SALT LAKE CITY — LeAnn Wood, a mom and member of the Utah State Board of Education, calls her son’s former school counselor “one of the heroes of our family.”

“She was there when we needed that extra support,” Wood said, noting that the counselor helped identify and address his social deficits when he was just in kindergarten.

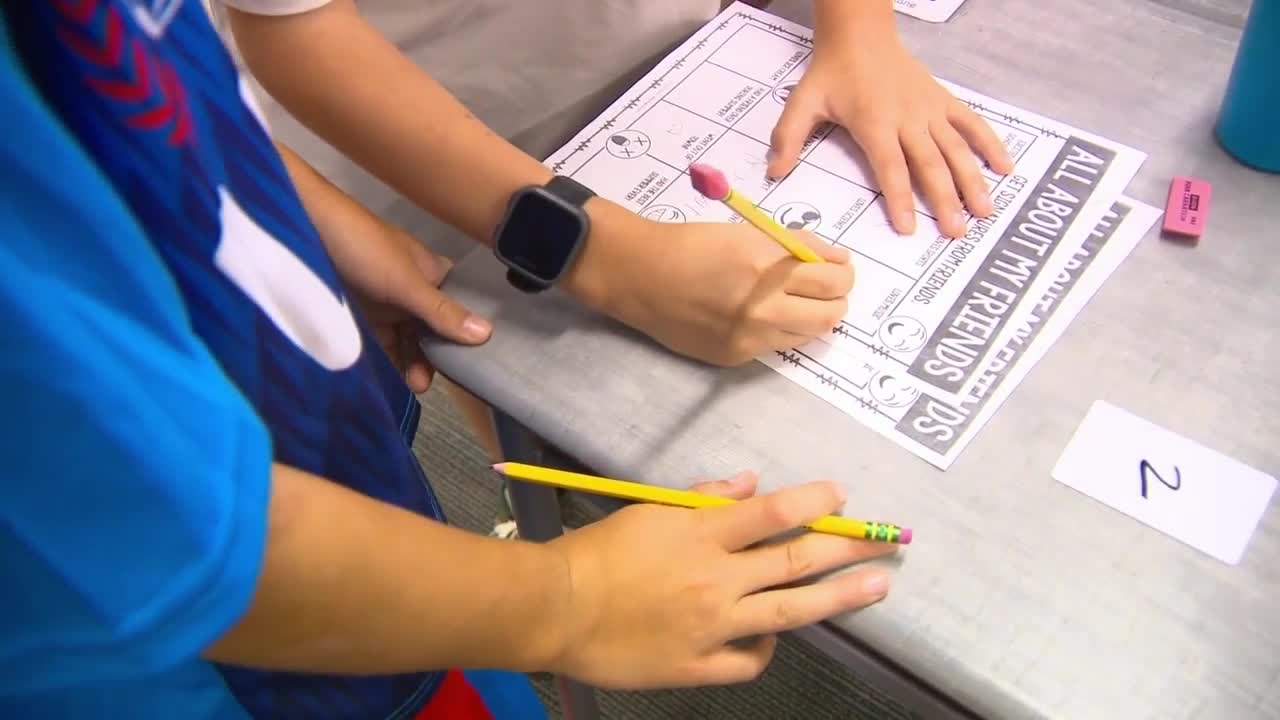

The counselor would open her office at lunchtime “for him to invite friends in to play games,” Wood recalled. And she “worked with him about that give and take and how to support other students and how to be friendly.”

Another of Wood's sons struggled with his mental health in high school. She credits a school psychologist with helping him work through grief after the death of his grandmother during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I love that the tools were in place for him to have that conversation with people that know how to work through that – the experts in the field of mental health – and that I had a place to turn to and they could do it at school,” she said in a recent interview with FOX 13 News.

School counselors and psychologists are seen as an increasingly important resource in Utah schools, especially as research shows more students are struggling with mental and behavioral health challenges.

But data shows the state doesn’t have enough professionals working in these roles – something that could make it more difficult for some students to access mental health support, especially in more rural parts of the state.

“Unfortunately, if there's not a mental health provider in that school, there is a gap in care for some of our students,” said April Zmudka, president of the Utah Association of School Psychologists.

Nearly 30% of Utah students in the eighth, tenth and twelfth grades experienced “serious mental illness” in 2023, according to a recent report on behavior and mental health commissioned by the Utah State Board of Education. About 7% reported attempting suicide in the preceding year. And nearly 19% reported having “seriously considered” attempting suicide in the same timeframe.

“They’re struggling to reach out to ask for help,” Zmudka said of the state’s students. “They don’t know where to go.”

School psychologists, she said, are uniquely positioned to identify and help support these students.

"That’s our bread and butter is working with kids who have really complex needs and helping them to be successful both at school and in life,” she said.

But there aren’t nearly enough of these professionals in the state’s schools. Data from the National Association of School Psychologists shows there are nearly 2,000 students for every one school psychologist in the state. The organization’s recommended ratio is one for every 500 students. Overall, Utah ranks 41st in the country for access to school psychologists, and about half of the state’s schools don’t have access to a full-time psychologist, according to the report prepared for the Utah State Board of Education.

The Utah Association of School Psychologists says these shortages can lead to a host of consequences, including “unmanageable caseloads,” an "inability for school psychologists to provide prevention and early intervention services” and “reduced access to mental and behavioral health services for some students."

Schools without psychologists are often located in more rural parts of the state, and Zmudka says other professionals have had to step up to fill the gaps – including school counselors and social workers.

“But they also have large caseloads as well,” she noted, as well as different professional backgrounds and training. “So they're having to find time in their very strapped caseload to support a student that otherwise wouldn’t get help.” There’s just one school counselor for every 500 students in Utah – about double the recommended number. And the ratio of social workers is even worse.

While Utah ranks low for access to mental health professionals in schools, many other states are facing similar challenges, according to Angela Kimball, chief advocacy officer at Inseparable, a group that advocates nationally for mental health policy.

That’s due, in part, to low numbers of students in the pipeline for these jobs, which she noted require a “great deal of training.” One way policymakers can help, she said, is by financially supporting these students' education and training.

“It's really an important area for lawmakers to look at,” Kimball said, “because I think a lot of times, people don't understand just how much of a financial barrier there is to going into these professions.”

Another challenge is the cost of staffing these positions. The behavioral and mental health report commissioned by the Utah State Board of Education noted difficulty “attracting and retaining qualified and effective staff given that there are more lucrative employment options available for specialized mental health and behavior professionals.”

The report said the annual average cost of a school psychologist is about $92,500, “while the average psychologist in Utah earns nearly 20% more at $110,630.”

“A lot of our larger school districts in the Salt Lake Valley area are desperately trying to fill more positions,” Zmudka said. “They want more school psychologists. They want more school psychologists in each individual school. But again, that comes with identifying funding to do so.”

Regardless of whether a school has a psychologist, counselor or social worker in the building, all students in the state have access to mental health services through the Safe UT app, which provides 24/7 support for students, including the ability to chat with licensed counselors or submit confidential tips.

Wood said her son used the Safe UT app a few times when he was struggling with his mental health in high school, and he credits it with saving his life twice.

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re Wasatch Front or rural,” she said. “that access to a licensed professional there just to talk to you can make a difference."

When schools do improve their access to mental health support, Kimball agrees that the impacts can be immense – even preventing some students from developing more serious issues as they grow up.

"When students — particularly adolescents — experience mental health challenges, too often they'll turn to alcohol or drugs to self-medicate, and that leads sometimes to devastating consequences,” she said. “When we're there in schools, we can help spot students who are struggling, extend a hand and help people get back on their feet.”