Organ donation saves thousands of lives every year, but recent headlines, social media posts and television storylines are creating confusion and concern about how the process really works.

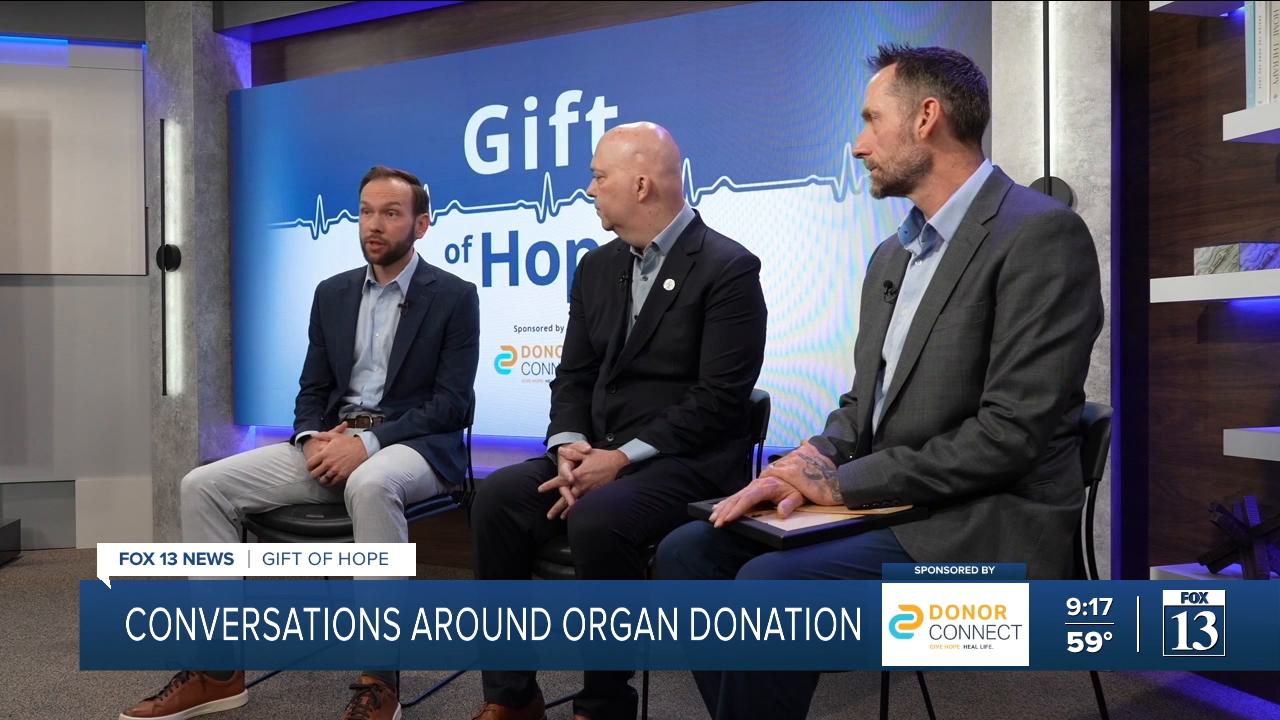

To help answer some of the toughest questions Utahns are asking, FOX 13 partnered with Utah’s organ procurement organization, DonorConnect, to assemble a panel of medical and donation experts to separate fact from fiction.

“OPOs are pretty much united in their cause. We’re here to save as many lives as possible,” said Dominic Adorno, president and CEO of DonorConnect. “What may be different is the partnership that we have with our hospitals here. Every OPO does its very best to maximize donation and support families, but they’re under different constraints from the system.”

Dr. David Dorsey, medical director of the University of Utah Organ Donation Program said Utah’s collaboration between hospitals and DonorConnect has helped maintain strong standards.

“The University of Utah is one of the hospitals that works with DonorConnect, and as a large area hospital, we have a pretty significant volume of organ donors,” Dorsey said. “Fortunately, here in Utah, our hospitals and our organ procurement organizations have historically done a very good job of working with donors and families and helping that process happen.”

One growing national concern involves the number of organs recovered but not ultimately transplanted.

“Technology has made more organs available than ever before,” Adorno said. “With that comes an imbalance, so there is a large number of organs currently that are being recovered for transplant that are not being used.”

Last year, nearly 9,200 kidneys recovered for transplant nationwide were not used. This year, Adorno said that number is on pace to drop to about 8,200.

“That’s something that’s going to improve over time,” he said.

Another topic drawing attention is brain death — and how it is determined.

“Brain death is complicated and it’s tough,” Dorsey said. “If someone completely loses blood flow to their brain, they’re no longer alive in a legal sense. And who they are as a person also lives in our brain. When the brain has been shut down with no chance of recovery, we declare those people deceased.”

Dorsey said the testing process follows strict national guidelines.

“We need to be perfect. There’s no room for error,” he said. “We double and triple-check everything because a mistake in brain death testing is potentially catastrophic.”

Both experts said television shows and online misinformation often oversimplify a highly complex medical process.

“We have a duty as physicians to do no harm,” Dorsey said. “We will never put a donor at risk in order to facilitate organ donation. And because of that, we lose organs, because the conditions have to be perfect.”

Adorno added that most deaths are not medically suitable for donation.

“It is a rare event. It’s resource intensive,” he said. “There’s a lot of work being done up-front — the testing to make sure that transplant will be safe for that patient.”

Despite record donation numbers in Utah, Adorno said recent media coverage has had an impact.

“With the recent media stories, we have seen a larger number of people take themselves off the registry,” he said. “These stories have had a negative impact on people’s perceptions of donation, and that’s why it’s very important for us to talk about this.”