For years, one vital blood vessel in the body has largely required open-heart surgery, even as less invasive vascular procedures became common elsewhere.

That vessel is the ascending aorta — the section of the body’s largest artery that rises directly from the heart.

“As this big blue heart rotates, the aorta is right there,” said Dr. John Doty, a cardiothoracic surgeon with Intermountain Health. “The heart and lungs take in blue blood. They give it new life, and then they return it through the ascending aorta. Every drop — clogging it means death — so it’s the highest stakes when surgery is required.”

Because of where it sits and how much blood flows through it, the ascending aorta has long been considered one of the most difficult places in the body to operate.

“The last frontier is the part of the aorta right on top of the heart,” Doty said. “And that’s a difficult place because that’s right where the blood comes out. There’s a lot of blood pressure. There’s a lot of motion.”

While vascular surgeons regularly treat arteries throughout the body, the ascending aorta has remained especially challenging — in part because it connects directly to the heart and moves with every beat.

“We always wind up on stories when someone hits the water main,” Doty said.

“Your analogy is excellent,” said Dr. Evan Brownie, a vascular surgeon at Intermountain Health. “That is the blood main coming right off there, and if you can’t repair that correctly, then it’s fatal.”

The heart’s constant movement adds another layer of complexity.

“The heart is right next to this thing beating in the chest,” Brownie said. “You’re watching the whole device move, and you have to either have a device that can allow that flow to go through it while you’re trying to deploy it, or have a mechanism of temporarily stopping, stunning the heart such that it’s not moving so much.”

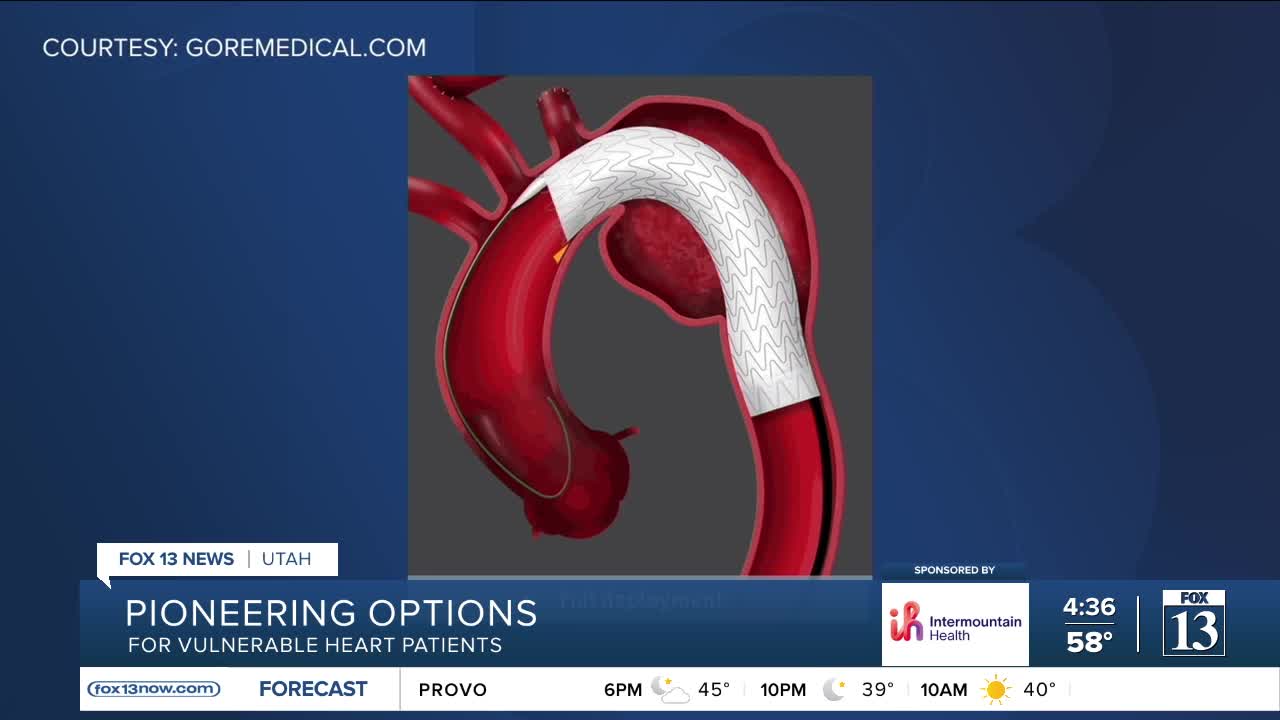

Now, doctors at Intermountain Health are part of a clinical trial testing a new graft device designed to treat the ascending aorta without traditional open-heart surgery. Using detailed imaging and careful placement, surgeons guide the device into the aorta, where it expands like a mesh sleeve to reinforce weakened or damaged vessel walls.

“The important thing to realize, though, is we are treating patients — and not the blood vessel itself,” Brownie said.

That patient-centered approach matters, especially for people with limited options. Utah’s first recipient of the graft had previously undergone emergency surgery for an aortic dissection and was not a good candidate for another major operation.

“This patient had previous emergency surgery for an aortic dissection,” Doty said. “These devices now can help us treat people that otherwise wouldn’t even be candidates for a big operation.”

By taking on the most challenging section of the body’s largest blood vessel, doctors hope the trial will help prove the safety and effectiveness of a treatment that could one day save — and extend — lives.