SALT LAKE CITY — Brian Coombs, founder of the OCD Foundation of Utah, started his journey with obsessive-compulsive disorder when he was just five years old.

“I had the strong urge to run back into home, and I felt the need to check lights, outlets, anything that could be on,” he said. "I felt like if I was the last one to see it and I had not checked it, perhaps it was my responsibility to make sure the house wouldn’t burn down.”

Symptoms lessened when he was a teenager, but came back full force in his 20s.

“I was serving an LDS mission, and struggled intensely during that time,” Coombs said. “Unfortunately, my mind was on this OCD that I couldn't stop.”

That’s when he realized he needed help.

“Ironically, right here in this office is where I came to therapy with the gal next to me, who's now in her mid-80s, and I received therapy from her,” Coombs said.

There are a lot of misconceptions around OCD.

“[One misconception is] everyone who has OCD is like the cleanest person on the planet. For some reason, that's a very common thing where everyone's like, 'Oh, but you're not that clean. I mean, there's clothes on your floor,'” said 24-year-old Alex Johnson. "I'm like, that's not what it is, though. That doesn't bother me. It would bother other OCD people, but for me, I could care less."

That, along with OCD itself, is what Johnson has also dealt with from a young age.

“You have a very painful itch, and no matter how much you scratch at it, it doesn't stop itching,” Johnson said.

“It could come in the form of really obsessive thoughts that are interrupting that person's ability to function on a daily basis,” said Dr. Matthew B Checketts with University of Utah Health.

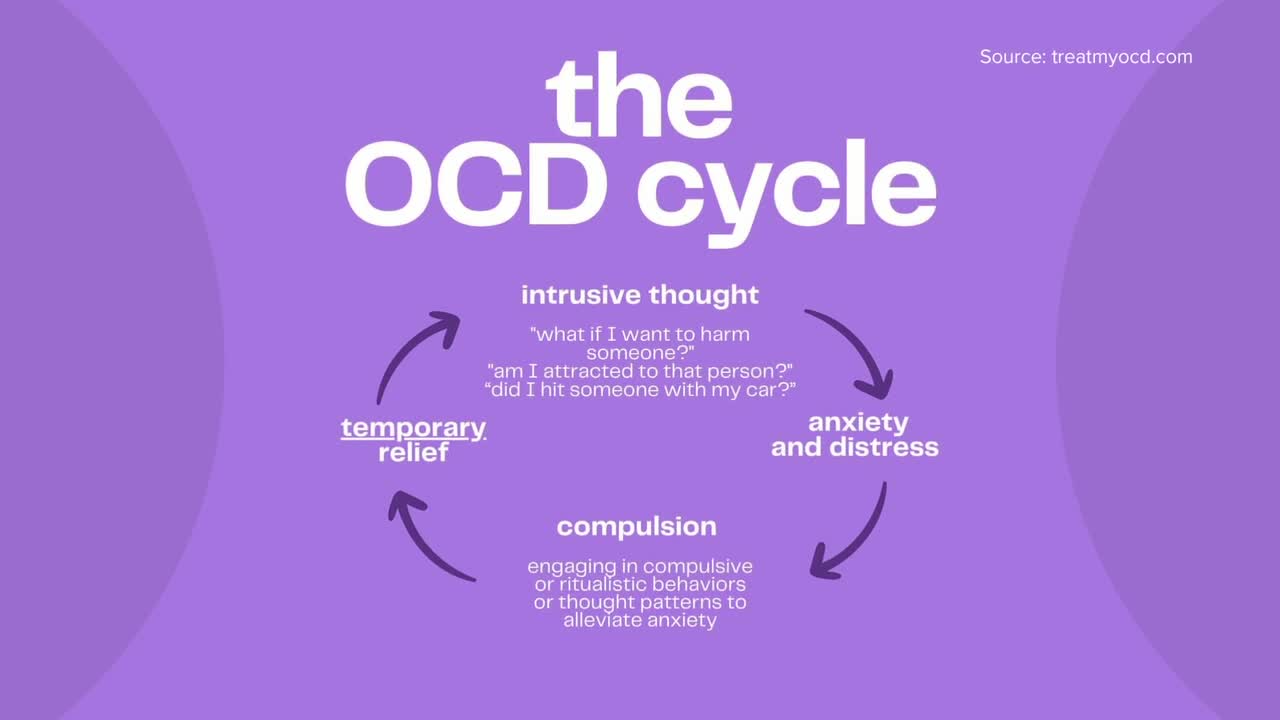

OCD often targets something people care about, such as relationships or their health. People with OCD might perform a compulsion that offers them temporary relief from an intrusive thought.

“We do the compulsion, which unfortunately maintains the disorder, keeps it telling the brain when I see this or this happens, or I feel this way, I must perform this behavior, and if I don't, the consequences can be catastrophic,” Coombs said.

In order to combat it, however, you need to treat the brain like a bully.

“Yep, maybe I did touch that thing. Oh, well,” Coombs said. "Once you address a bully, bullies don't like that. They want that control, and OCD is very similar. It wants control, and so if you can accept the urge to perform a compulsion, push back by leaning into it, that bully starts to cower.”

OCD often goes undiagnosed, and Coombs wants parents to be aware if their children are constantly asking for reassurance or performing repetitive behaviors.

“It gets frustrating when they're asking for reassurance. So much so, we just kind of throw them a bone and give them the answer. The problem with that is it comes back each time the brain wants that answer, so education is key,” Coombs said.

While OCD is a big obstacle, Coombs would tackle it again to meet all the people who have come into his life since.

“If the world's ending and there's a team that I would put together, it would be from my clients. They are the type of people that do most anything for anybody; they feel so deeply,” Coombs said through tears.

To learn more about the OCD Foundation of Utah, visit: brian-coombs.squarespace.com

Additional information about OCD and resources can be found on the OCD Foundation of Utah's website, treatmyocd.com or iocdf.org.